In this article Kelly A. Koch, Esq. discusses digital money, known as cryptocurrency, and a divorce.

Over the last two decades, divorce practitioners have become familiar with various ways litigants can earn income, transact in payment systems or acquire additional assets. PayPal, eBay, Venmo, CashApp and Apple Pay are just a few of the “newer” financial accounts that attorneys have had to understand, incorporate into discovery requests and ensure are included on their clients’ Rule 401 Financial Statements. It’s time for practitioners to add one more financial aspect to their domestic relations cases involving financial issues – cryptocurrency.

Cryptocurrency primer

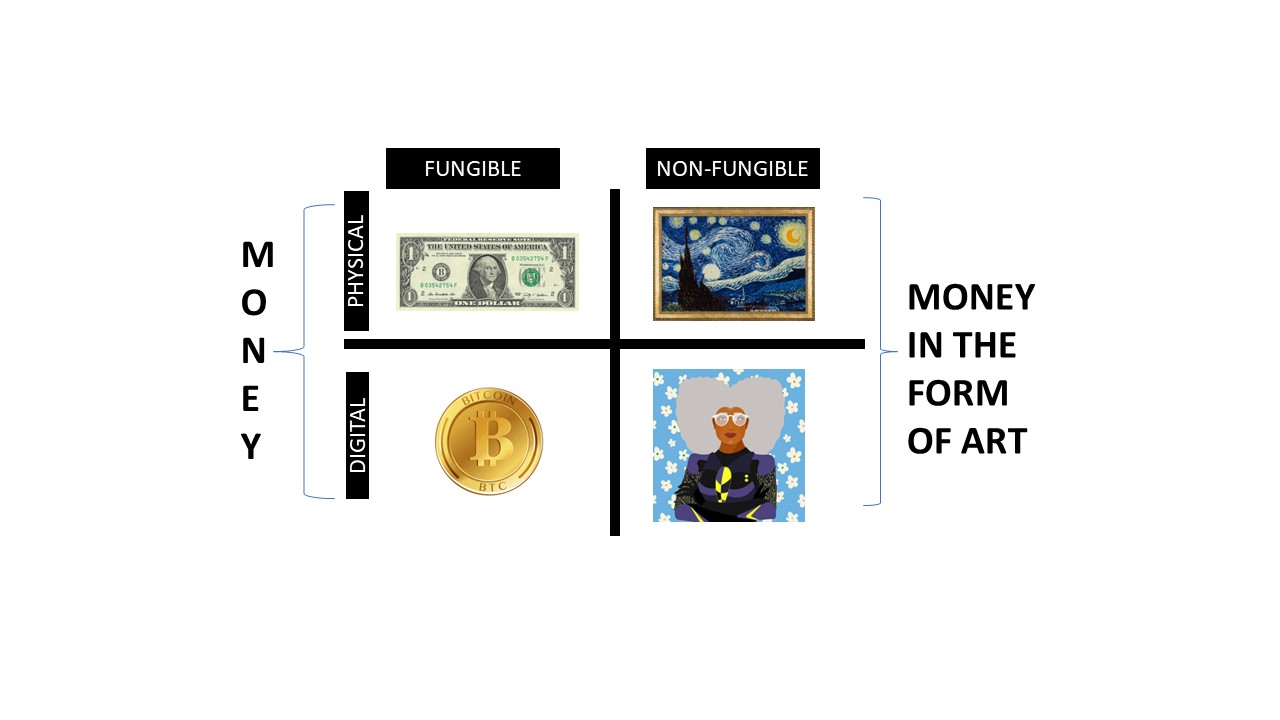

Cryptocurrency, also known as virtual currency, is digital money known for its secure nature and anonymity. Just like there are many types physical or “fiat” currencies (think coin and paper money) used all over the world (i.e. Yen, Euro, Franc, Dollar), there are thousands of cryptocurrencies.

The first cryptocurrency – Bitcoin – was launched in 2009 and remains the most popular token worldwide. While most people store their fiat money in banks, those who own cryptocurrency primarily store their assets in 16-digit encrypted online wallets. A digital wallet is a mixture of letters and numbers that allow a person to purchase cryptocurrency from a centralized exchange (think Coinbase, Robinhood or Gemini) or transfer cryptocurrency or digital assets between different wallets.

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency transactions are included in an infinite digital file akin to a running ledger. For each cryptocurrency, every single transaction is validated by multiple people who use their computers to create “nodes” and verify transactions. Once completed, the data from a cryptocurrency transaction is added to the “blockchain,” which cannot be altered. Those who validate the data are called “miners” and are paid for their work in Bitcoin or another cryptocurrency. The blockchain for each cryptocurrency can be viewed on any computer – so if you are reading this article on a computer or mobile device, you also have access to the blockchain!

Ethereum is the second most popular cryptocurrency and has a completely different use compared to Bitcoin. While Bitcoin is primarily thought of as a digital alternative to fiat currencies and a store of value, Ethereum is far more versatile.

Three of the most popular uses for Ethereum include decentralized finance (DeFi), smart contracts and non-fungible tokens (NFTs). Instead of simply using Ethereum as a store of value, a person can use Ethereum to create smart contracts for a variety of purposes including streamlining digital identity, real estate transactions, and ticketing for events. The one-of-a-kind output code from the contract provides proof of ownership (“provenance”) and that is forever on the blockchain.

Arguably the most popular use for Ethereum involves NFT creation and transactions. NFTs can represent anything digital in nature including but not limited to art, music, diplomas, and artificial intelligence. NFTs are each unique and represented by a specific “token” on the blockchain. NFT art ownership is easily proven on the blockchain used to purchase the art (e.g. Ethereum) and typically purchased on centralized marketplaces like OpenSea, LooksRare or Blur.

Intersection of Cryptocurrency and Divorce

While cryptocurrency might be a newer issue for practitioners, the intersection of cryptocurrency and divorce is firmly rooted in black letter law and precedent. (e.g. G. L. c. 208, §34; Supp. Prob. Ct. Rule 401; Baccanti v. Morton, 434 Mass. 787 (2001), and Mass. R. Dom. Rel. P. 26, 33, 34 and 45).

Massachusetts courts take an expansive approach when it comes to assets that are part of the marital estate. In fact, a Probate and Family Court judge is not “bound by traditional concepts of title or property (even those not within the complete possession or control of their holders) to be part of a spouse’s estate for purposes of §34.” Baccanti, supra at 794. Additionally, §34 provides that “the court may assign to either husband or wife all or any part of the estate of the other…” (emphasis supplied).

The value of cryptocurrency and NFTs must be listed on a party’s Rule 401 Financial Statement. Failure to disclose could result in dire consequences considering a judge may take “reasonable inferences against a party who fails to” make adequate financial data available to the other spouse. Grubert v. Grubert, 20 Mass. App. Ct. 811, 822 (1985). Failure to disclose can also subject a party to a post-divorce §34 division of the marital estate based upon fraud and/or misrepresentation.

Cryptocurrency as an Asset to your Divorce

The owner of cryptocurrency and NFTs is in the best position to provide the data needed to accurately assess its value. Even if a party is not forthcoming about the disclosure of cryptocurrency and NFTs, there are plenty of places a lay person can look for clues. Some suggestions include:

- Bank statements from a party’s Rule 410 production will show deposits from centralized exchanges into a bank account or a deposit from a bank account to a centralized exchange to purchase cryptocurrency;

- Some cryptocurrency can be purchased via credit card, so a Rule 34 Request for Production of Documents for credit card statements would be helpful;

- Certain centralized exchanges based in the United States provide 1099s to users. Coinbase will generate a 1099-MISC if a user “earns” more than $600 annually. Coinbase does not report transactions directly to the IRS, but it will respond to subpoenas. Additionally, you can download raw transactional data from a user’s profile into an Excel spreadsheet;

- Requests for Production of Documents can request AppStore transactions to determine whether someone has downloaded cryptocurrency/NFT apps (i.e. Coinbase, MetaMask, OpenSea, Robinhood, Gemini etc.) as well as emails generated from centralized exchanges regarding cryptocurrency and NFT transactions;

- Tax returns have multiple places that could signal cryptocurrency and NFT transactions:

- First page of the 1040 has a box above the “Standard Deduction” section that asks if at “any time during the last tax year did a taxpayer receive, sell, exchange or otherwise dispose of any financial interest in any virtual currency?”;

- Line 7 on the first page of a 1040 denotes capital gains or losses;

- Schedule D from a 1040 details all transactions that trigger capital gains or losses. Cryptocurrency and NFT transactions are includable; and

- Form 8949 from a 1040 specifically highlights sales and other dispositions of capital assets, which includes cryptocurrency.

Sending out electronic preservation letters may ensure that a litigant does not destroy or alter devices used to transact in cryptocurrency and NFTs. Pursuant to Mass. R. Dom. Rel. P. 34, a party can be required to bring devices used for cryptocurrency transactions to a deposition. For the more dilatory or obstructionist opposing parties, a forensic computer analyst can make digital copies of devices and analyze transaction history to glean wallet identification, purchases and sales, as well as evidence showing a hard drive was utilized to move cryptocurrency or NFTs. If you are able to obtain a party’s cryptocurrency wallet information or account “handles,” anyone with a computer can access the relevant blockchain and examine transaction history.

Just like the stock market, the value of virtual assets changes second-by-second. Every time cryptocurrency is bought, sold or transferred, its value will very likely be different than the time of purchase. Additionally, all cryptocurrency transactions are taxable events because the IRS considers cryptocurrency and any digital asset to be “property.” Knowing the value of the cryptocurrency at the time of purchase and the time of sale is necessary in order to determine whether or not long-term or short-term capital gains taxes must be paid or losses declared. (see IRS Notice 2014-21)

Only after obtaining and synthesizing the information pertaining to the amount and value of a party’s cryptocurrency and other digital assets can one make an educated decision about how to divide them. It is wise to employ a CPA or another qualified person to examine potential options that maximize division in your client’s favor while also taking into consideration any possible tax consequences.

Even after you have a full grasp of a person’s cryptocurrency holdings and understand the tax implications, consideration must also be given to the valuation and division dates. For example, if John Doe, while married, purchased one Bitcoin on March 15, 2019, it would have cost approximately $3,947. John filed for divorce on March 15, 2020, and his one Bitcoin had an approximate value of $5,625. If the divorce trial took place on March 13, 2021, the value of one Bitcoin was approximately $61,207. At the time the Court issued its Judgment of Divorce Nisi on July 15, 2021, the value of Bitcoin was $32,857.

It is likely that one party would like to value the Bitcoin as of the date of trial while the other would prefer either the date of division or date of filing. The trial and judgment dates reflect a difference in value of about $28,000, whereas the date of filing and the date of divorce results in a difference of about $55,500. To equitably deal with this matter, it might be helpful to use the if and when received method from Baccanti, supra at 802. Another possibility is to divide the asset during the pendency of the divorce as a “predistribution” of sorts that allows the parties to convert to USD based on their risk tolerance.

What’s next?

Should you or someone you know need assistance filing for a divorce and dividing digital assets like cryptocurrency, schedule a free consultation with Attorney Kelly Koch. Book a free consultation here.

More Resources

https://www.wealthmanagement.com/high-net-worth/finding-and-dividing-hidden-crypto-assets-divorce

https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/digital-assets